What Are Common Oral Health Problems in Seniors?

In this article

Persistent oral health issues affect millions of older adults in the United States. From tooth loss and gum disease to dry mouth and oral cancer, these challenges are not just a matter of comfort; they’re closely tied to systemic health and quality of life.

This article offers a clear, data-backed look at the most common oral health problems affecting seniors and how these trends have evolved from 2019 through 2025.

The following statistics offer a snapshot of oral health conditions among adults aged 65 and older in the United States.

Aging affects every part of the body, and your mouth is no exception. Several normal physiological changes raise the risk of oral health problems.

Saliva production tends to decrease with age, especially in people taking multiple medications. This condition, called dry mouth (or xerostomia), weakens the natural defenses that protect teeth from decay and the gums from infection.

At the same time, the gums naturally recede, exposing root surfaces that lack protective enamel. These shifts don't guarantee problems, but they do make preventive care more important.

The most common oral health issues in older adults are distinct from those seen in younger people. The conditions below cause pain, interfere with eating, and increase the risk of other health complications.

Root caries refers to decay on the tooth root, which becomes exposed due to gum recession.

Unlike enamel, the root surface is covered by a softer material called cementum. This makes it more vulnerable to acid damage—especially when dry mouth limits the protective effects of saliva.

According to national data, root caries affects 16% of older adults and up to 33% of those with low incomes.

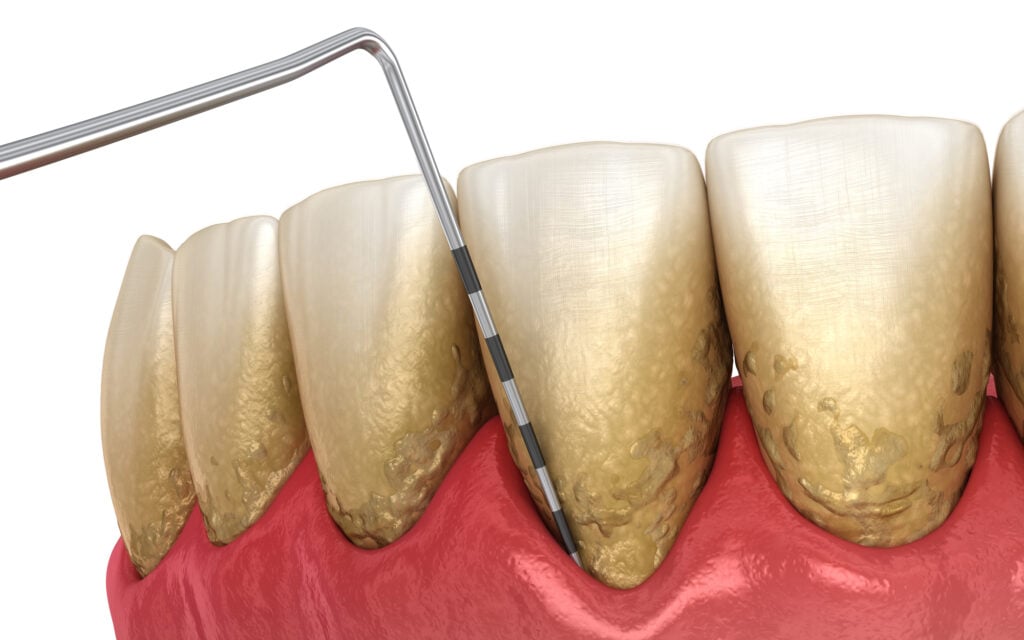

Periodontitis is an advanced form of gum disease that leads to inflammation, infection, and loss of bone and tissue around the teeth.

In the most recent CDC data, nearly 60% of seniors have some form of periodontitis. Rates increase with age: 71.5% of adults aged 65–74 and 81% of those 75 and older show signs of the disease.

Beyond the mouth, chronic inflammation from periodontitis has been linked with diabetes complications and cardiovascular risk.

Tooth loss still affects many older adults, though less so than in previous generations. In 2017–2020, the average number of remaining teeth was 21.7 for adults 65–74 and 19.8 for those 75+.

Complete edentulism (having no natural teeth) was found in 11.4% of seniors aged 65–74 and 19.7% of those aged 75 and older.

Tooth loss impacts nutrition, speech, and quality of life, especially when replacement options are unaffordable or inaccessible.

Oral and oropharyngeal cancers are increasingly common in the senior population. In 2025, an estimated 59,660 new cases and 12,770 deaths are projected nationwide.

The incidence rate for adults 75 and older reaches 44.8 per 100,000 people. Survival is highly variable: 55% of white adults survive five years after diagnosis, compared to just 33% of Black adults.

Oral health disparities vary across the country. Access to preventive care, insurance coverage, and state policy shape these outcomes.

| Region | Metric | Year | Value |

| National | Untreated Caries (65+) | 2017–2020 | 13% |

| National | Periodontitis (65+) | 2017–2020 | 59.8% |

| National | Edentulism (75+) | 2017–2020 | 19.7% |

| New Hampshire | Medicaid Dental Benefit | 2019 | Emergency only |

| New York | Medicaid Dental Benefit | 2019 | Extensive |

| Utah | Medicaid Dental Benefit | 2025 | Extensive |

Top/Bottom Patterns:

These patterns reflect how state-level decisions affect care access.

While many older adults retain more natural teeth than in the past, trends show ongoing challenges.

Between 2014 and 2022, the average annual rate of emergency department visits for tooth disorders decreased from 88.4 to 59.4 per 10,000 people.

This reflects better preventive access in some areas, but also suggests that seniors may delay care until problems are severe.

Tooth retention has improved, but disparities persist. From 2017 to 2020, complete tooth loss was nearly twice as common in those aged 75+ (19.7%) compared to those aged 65–74 (11.4%).

Some seniors are more vulnerable to oral health problems due to long-standing disparities in income, education, race, and physical ability.

In 2022, only 35.3% of older adults living below the federal poverty level visited a dentist, compared to 80.5% of those with incomes over 400% of the poverty line. Education shows similar effects: dental visit rates ranged from 33.3% for those without a high school diploma to 82% for college graduates.

Racial disparities persist as well. More than half (52%) of Black adults have lost at least one tooth due to decay or gum disease, compared to 43% of all adults. Five-year survival rates for oral cancer are markedly lower for Black seniors (33%) than white seniors (55%), suggesting inequities in early detection and treatment.

Geography also matters. Older adults in rural communities often face “dental care deserts” with few nearby providers, limited transportation, and inconsistent Medicaid coverage.

Long-term care facilities face their own barriers. Only 16% of nursing home residents reportedly receive daily oral care—a problem often linked to staffing shortages and a lack of caregiver training.

These disparities are not just about teeth. They reflect broader inequities in health care access, resources, and outcomes.

Access to oral health care in older adults is closely tied to insurance status. In 2022, 69.6% of seniors with dental insurance had seen a dentist in the past year, compared to just 56.4% of those without coverage.

Unfortunately, traditional Medicare does not cover routine dental care. Coverage is limited to “medically necessary” procedures, such as dental exams before organ transplants or treatment of infections prior to heart surgery. Medicare Advantage plans may offer expanded benefits, but access remains inconsistent.

Medicaid is different. Each state decides whether to cover adult dental services. Some, like New York and Utah, provide extensive benefits. Others offer only emergency services—or none at all. Between 2019 and 2025, several states (e.g., Utah, Virginia) expanded their Medicaid dental offerings, setting examples for others to follow.

Community health centers (FQHCs) also play a vital role. They provide dental services on a sliding fee scale, and many offer care tailored to older adults. However, appointment availability and service scope can vary.

Understanding oral health data requires clarity on how conditions and metrics are defined.

Rates may be reported as:

This article draws from national datasets covering the years 2017 through 2025:

Data handling:

In this article